Saint Nicholas: Teacher of Faith

by Gerardo Cioffari, o.p.

The popular image of St Nicholas does not always correspond to that of the official Church. And this happens not only among Catholics, but even among Orthodox and Protestants. In the case of St. Nicholas this is especially more evident. The differentiation did not happen, as it could be thought, after the year 1054 (Catholic-Orthodox schism) or after 1517 (Catholic-Protestant schism), but long before. In fact the different approach does not depend upon faith or dogma, but upon the different ways of life and culture.

Ivory case, Museo Civico Medioevale, Bologna, Italy Photo: Sailko, Wikimedia Commons,under CC Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license |

People everywhere see Nicholas as the Saint of charity, toward the poor girls or those who are in need. However, Churches in their liturgies, without forgetting this aspect, point out and underscore other particular virtues. The Catholic Church looks at him as ideal bishop of mercy. The Orthodox Church sees in him the defender of true faith (orthodoxy: Kanona pisteos, Pravilo very). The Protestant churches love him and, on the wave of the Hanseatic league, have seen him as defender of the honest property (hence his churches in the market places or along the sea or rivers).

The Orthodox image of Nicholas as teacher of faith (almost absent in Catholic or Protestant liturgies), at first sight could appear strange, considering the fact that no Nicholas' writing is known. However, this perspective should be reviewed, because historical sources are not only the literary texts, but also ecclesiastical traditions. Liturgy is historically very important because the spirit of ancient Christianity was based on tradition, on the belief that nothing should be changed. I do not know in Greek, but in pre-revolutionary Russian theological works it was more the word "novovvedenie" (the introduction of novelty) than the word "heresy".

If this is an obstacle for Orthodoxy to to walk with the times, for the historian is an advantage. That's why I believe that the editor of the Greek texts, Gustav Anrich, made a mistake neglecting liturgical texts and tradition. It was a legitimate thing to do, if afterwards he had restrained from giving historical conclusions. Historical criticism in hagiography, if you neglect liturgy, is unsteady. Liturgy is necessary, because it does not start with the IX century, as Anrich and Delehaye give the impression to believe when speaking of Synaxaria. IX century liturgy is not a creation, but an elaboration and development of previous centuries texts, not a new creation, as it seem to suggest this inscription in Gortina (Crete, Greece) of the VI century.

On the other hand, the most ancient sources are clear about this. The Praxis de stratelatis (IV century), as soon as it speak of Nicholas, qualifies him as ο της εκεισε αγιας εκκλησιας ποιμην και διδασκαλος, the pastor and the teacher of that Church (of Myra). Later, Michael the Archimandrite and Andrew of Crete (VIII century) speak of the Gospel catechesis of Nicholas among the Myrian population, that still believed in pagan gods. To express this concept Michael narrated the episode of the destruction of the patron goddess of the city, Artemis. Therefore, both Michael and Andrew do not see Nicholas launched against just one error, rather he proceeds to an overall true sound catechesis.

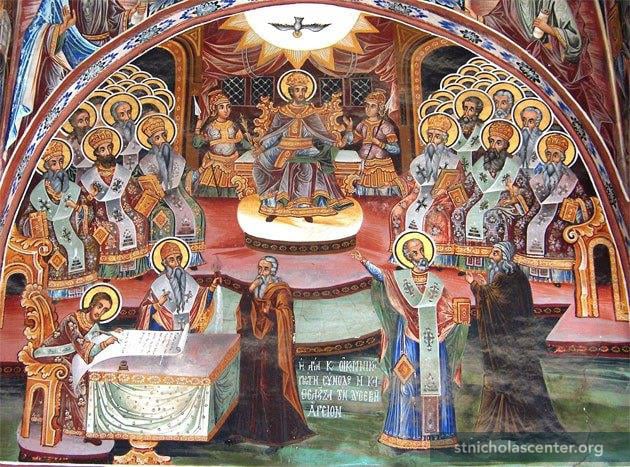

Very often writers have seen Nicholas engaged against Arius (fantasizing even a slap to the leader of this heresy). But Michael and Andrew say that he fought both heresies: the one by Sabellius, because to save God's unity, this heretic saw Christ and the Holy Spirit not as persons, but as ways in which the Father appeared to men; the other one by Arius, because of the opposite mistake, underscoring the distinction of God the Father and the Son, this heretic, his contemporary, made the Son a creature that the Father at a certain moment has deified. St Nicholas fought both mistakes. He defended the doctrine that came out of the ecumenical council of Nicaea (AD 325).

The extraordinary importance of St Nicholas in Byzantine liturgy is revealed primarily by his role in the Parakletiki (the office of ordinary Thursday) and in the iconographical richness (he is sometimes even in the Deesis of the central apse, together with John the Baptist, or at his place).

Photo: C Myers, St Nicholas Center |

The most known St Nicholas' prayer is the Apolytikion "Rule of faith:"

As a rule of faith (Κανονα Πιστεως, Правило веры),

the truth of things revealed thee to thy flock,

as an icon of meekness, and a teacher of temperance;

therefore thou hast achieved the heights by humility,

riches by poverty.

O Father and Hierarch Nicholas,

intercede with Christ God that our souls be saved.

Less known, but equally important, is the fact that liturgy and iconography have transmitted an image of the Saint in company with the great Fathers of the Church, the ecumenical or universal (oikoumeniki, vselenskie) teachers Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian and John Chrysostom, who were those who gave the theological formulation to the Faith professed today by Catholics, Orthodox and Protestants.

At the Litija (Processional litanies) of the Great Vespers there are two prayers, one said by the deacon ((Σωσον, ο Θεος, τον λαον σου), the other by the priest ((Δεσποτα πολυελεε), that differ at the beginning till "Virgin Mary," and coinciding till the end.

O God, save thy people, and bless thyne heritage. Visit thy world with mercy and bounties; exalt the horn of Orthodox Christians, and send down upon us thy rich mercies. Through the prayers of our all-undefiled Lady, the Birth giver of God and ever-virgin Mary: through the might of the precious and life-giving Cross; through the protection of the honorable bodiless Powers of heaven; of the honorable, glorious Prophet, Forerunner and Baptist, John; of the holy, glorious and all laudable Apostles; of our holy Fathers, great Hierarchs and Oecumenical Teachers Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian and John Chrysostom; of our holy Father Nicholas, Archbishop of Myra in Lycia, the Wonder-worker; of our holy Fathers; of our glorious right-victorious Martyrs; of our reverend and God bearing Fathers, the holy and righteous ancestors of God, Joachim and Anna; of Saint [the Patron Saint of the temple]; and of all thy Saints: we beseech thee, o all merciful Lord, give ear unto us sinners, who make our supplications unto thee, and have mercy upon us.

A little afterwards the Priest says the same prayer, changing only the beginning till "Virgin Mary":

O Lord of great mercy, Jesus Christ our God, with the intercession of the all pure Lady, our Mother of God and forever Virgin Mary . . .

Because of the importance of this prayer, the Greeks and the Russians, as well as the Greek-Catholics of Ukraine, after the mention of St Nicholas, add the most significant Saints of their land.

As it is well known, the only literary hint to Nicholas as teacher is in the Encomium by Andrew of Crete, written few years after 700 AD. This famous composer of canons narrates St Nicholasf theological clash with the bishop Theognis (this was the name of the bishop of Nicaea) to whom he wrote. Because among them were pronounced harsh words, Nicholas concluded for peace: Let the sun not to go down on our anger. In other words, according Andrew of Crete, St Nicholasf engagement for truth (the Son consubstantial to the Father) did not imply a lack of charity. He was a defender of Faith, but without excommunications. And it is exactly for this keeping together truth and charity that, bypassing centuries of misunderstandings and wars among Christians, St Nicholas figure became the center of the ecumenical movement.

Photo: The Blago Fund, used by permission |

St Nicholas' doctrinal engagement was carried out through the catechesis to the people of Myra. The first biographers saw his fight to the pagan religion in the demolition of Artemis temple. In the IV century there were some fathers of the Church that arrived to destroy pagan temples, but it is difficult to say whether St Nicholas destruction is to be taken literally.

The most important list of the Fathers who were present at the Council of Nicaea (325) was compiled by Theodore Anagnostes (the Lector) about 520 AD. St Nicholas occupies the 151st place. Ms Gr. 344 f. 37v of the Marciana (Venice)

With the exception of his presence at the Council, all the episodes narrated afterwards (and especially the slap to Arius) are pure legends.

The biographers of St Nicholas of the past centuries not only invented many episodes without any historical ground, but sometimes they borrowed them from other Saints. For example, the episode of the brick was taken from the legend of St Spiridon.

By Fr Gerardo Cioffari o.p., Director of the St Nicholas Research Center, Basilica Pontificia San Nicola, Bari, Italy, St Nicholas News, N. 141, May 25, 2021. Used by permission. ,