Manna or Myron

from the Basilica Pontificia San Nicola, Bari, Italy

From the sacred urn of Nicholas, placed with his relics perhaps in the floor of the cruciform martyrium annexed to the basilica of Myra, it was believed that, immediately after his death, an extraordinary liquid, called myron, began to flow, certainly related to the fragrant essences found throughout the area, from which the city itself took its name.

Photo: Elio Sciacovelli |

In the Mediterranean hagiographic panorama, the exudation of liquids from saints' relics was not uncommon: Saint Andrew in Patras dripped "manna" on his feast day, as did Saint John in Ephesus and Saint Demetrius in Thessaloniki (oil and manna in the form of flour), Saint Euphemia in Chalcedon dripped blood, and Saint Hyacinth in Amastris a curiously violent jet of dust. Everything was collected by the pilgrims in small containers and vials (eulogies, that is, blessings): water, dust, manna, oil, wax, to be brought back home not only as a souvenir and certificate of the pilgrimage completed, but also as a pledge of the assiduous protection of the martyr whose tomb had been venerated.

In Myra, the sarcophagus of Saint Nicholas let myron flow (from the bones or from the tomb?) (which was collected with a feather, that is, in small quantities), which nevertheless became the most famous liquid of its kind, so much so that it attracted a large number of pilgrims for that phenomenon.

Unfortunately, not even one eulogy of Saint Nicholas (from the 5th-6th century) has survived, unlike the numerous ones of Saint Menas of Alexandria in Egypt, Saint Thecla of Antioch, Saint Simeon Stylites in Syria, Saint Phocas of Sinope, Saint Demetrius of Thessaloniki, preserved in the Museums of Bobbio, Monza, Farfa, London, Paris, Sassari, with the stamping of the images of the Saints or decorated with crosses, stars, flowers, palmettes, praying figures or some scene or emblem synthetic of the life and miracles of the venerated martyr. Some even contain a model of the sanctuary visited (Palestine, Ephesus, Delos).

In the East, John Chrysostom already mentions the distribution of such ampoules in a homily addressed to pilgrims: "Stop at the tomb of the martyrs, shed rivers of tears, chastise your heart and take the eulogia with you. Take the holy oil, so that your body may be anointed with it, your tongue, your lips, your neck, your eyes." A rather extensive eulogia for such a vast anointing!

Regarding Saint Nicholas, his first biographer, Michael the Archimandrite, around 710-720, connects the "fragrant and fragrant conduct" of the Saint in life to his "precious body, fragrant with the fragrances of virtue" and the resulting exudation of "a fragrant and sweet oil, which drives away every evil and is good for providing a remedy that saves and repels evil", referring to a generic conceptual context rather than a specific thaumaturgical one.

It should be noted that myron, rather than an oily liquid, is made up of pure water, but its nature was probably rather doubtful at the time.

In the West, the first writer to mention the "manna" of Saint Nicholas is John of Amalfi (around 950), followed by others who emphasize the miracles performed by its flow and the impact of the miracle on the crowds of pilgrims.

One of their writings contains a picturesque illustration of the tomb of Saint Nicholas in Myra ("in an elevated place to the right of the church hall"), which unites the flow of two elements, oil and water, in the same tomb: "As we ourselves have observed, two streams spring forth which have not ceased to flow to this day. From the source, at the height of the sacred tomb, flows a clear, oily liquid; from the stream flowing at the feet, a sweet, transparent water flows which, if given to the sick to drink, restores their bodily health."

The vial described by Hrabanus Maurus in a poem composed in 816 about seventeen relics preserved on the tomb of Saint Boniface was instead full of "myrrh."

When the people of Bari stormed the basilica of Myra, the monks guarding the sanctuary, believing them to be pilgrims, albeit somewhat noisy, offered them a small amount of holy "liquor" extracted from the tomb, collected like oil in a glass vial by the presbyter Lupo. And when the sarcophagus was opened, young Matthew first immersed his hands in search of the bones covered in that "liquor," reaching halfway into the tomb and then his entire body, soaking his clothes in the "health-giving latex."

It is known that that liquid was left to the people of Myra for their own wretched consolation: "You should be abundantly consoled by the fact that you have with you a tomb full of holy liquid, left especially for you."

The Kiev Chronicle, however, speaks of manna: "They found the urn full of manna. They poured the manna into wineskins and took the relics." Those wineskins, if they were indeed used, represent the oldest examples of the "manna bottles" of Bari.

Nothing is known about the prodigious effusion during the two years the sacred remains were kept in the church of Santo Stefano. But after their solemn repositioning in the crypt, the quintessential "manna" began to flow abundantly again, even though the Saint's Responsory returns to the theme of oil ("cuius Tumba fert oleum, matris, olivae nescium; quod natura non protulit, marmor suando parturit" ("Whose tomb bears oil, unknown to the mother, the olive; what nature did not produce, marble gives birth to by sweating")).

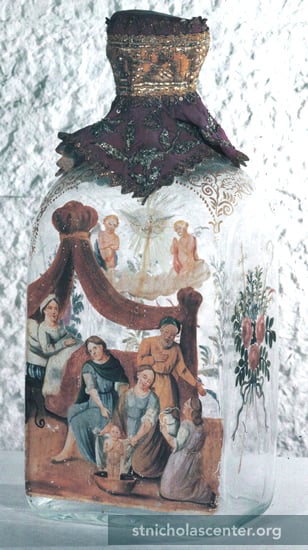

Whether oil or water, the people of Bari, over time, hoarded it, to store it in the graceful "bottles" painted with the image and scenes from the life of Saint Nicholas, of great variety and type.

Manna of Saint Nicholas

Scientific documents on the nature of the manna

"Manna" in the most ancient Greek testimonies

In another section

Prayers for the Administration of Saint Nicholas Manna

Links

Short clip, also from www.st-nicholas.tv

The "La Manna o Myron," Basilica Pontificia San Nicola, Bari, Italy, used by permission.